Miriam, Moses, and the Mumpsimus

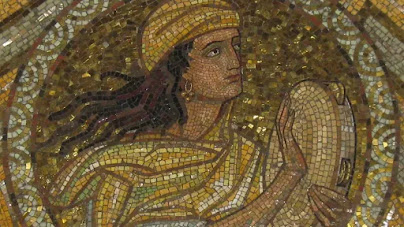

Mosaic from the Abbey Church of the Dormition in Jerusalem

There is a story about a mistake made in Latin, in a Catholic mass, in the 16th Century. The story is of a priest who, when reciting the mass in Latin for his congregation, got into the bad habit of saying the word mumpsimus instead of sumpsimus. Sumpsimus means “we have taken”. Mumpsimus, on the other hand, doesn’t mean anything at all. Despite being corrected, so goes the story, the priest stubbornly stuck to his mistake. His masses were always conducted with the nonsense word mumpsimus, and he could not be talked out of it.

Now mumpsimus does have a meaning. It means someone who obstinately sticks to their opinion even after being shown that they are wrong.

It is a cute story in part because, at least to most of us, it doesn’t really matter. We’re people who pray in a language which isn’t our mother tongue. Even for native Hebrew speakers, the language of prayer is not precisely the same as the language of speech. So which of us hasn’t come across something we’ve slightly mispronounced?

But of course, the problem in the story of the mumpsimus was never the mistake. It was how to react when faced with evidence that we might not be correct.

I like telling the story of mumpsimus, and not only because it’s a fun non-word to say. I like it because it reminds me of Pharaoh in these parshiyot, faced with the reality of the power of God and the necessity of letting the Israelites go. Pharaoh, who just cannot make the paradigm shift and realise he was wrong. Pharaoh, who keeps returning so stubbornly to a deathly case of mumpsimus.

But it is also, I think, a particularly difficult story to encounter in the age of misinformation campaigns. How are we supposed to know when we are wrong when evidence put before us is so often propaganda? When images themselves might be real, or might be from another war entirely, or might be AI? The mumpsimus priest was not faced with an onslaught of other clergymen telling him that mumpsimus was always the correct pronunciation. And the mumpsimus stakes were a lot lower than those we are facing today.

I know I am not the only one in this room who is kept up at night sometimes with the question: what if I am wrong?

On the one hand… maybe it is a good thing. After all, Pharaoh’s problem is a continual hardening of his own heart, a heart-hardening of which he quickly loses control. The more we say “no, I am correct” - the more we isolate ourselves in echo-chambers and surround ourselves with information that fits our preconceived narrative - the harder it is to account for any information that does not fit. I think most of us can probably recognise that in other people when we think their opinions are wrong. So maybe doubt is a good thing as a protective measure against falling into our own extremes.

But… on the other hand. On the other hand, doubt may lead us into ceding to evil. On the other hand, what happens if we are constantly negotiating our values with people who continually move further and further into extremes? What happens is that the “middle ground”, so often lauded as the correct place to be, keeps shifting in their direction. Moses cannot give into Pharaoh’s demands. He cannot negotiate to take only half the Israelites with him and leave Pharaoh some slaves behind. We have to resist negotiating our values to be closer to the values of those who would see us destroyed.

Both of those things can be true. Doubt, uncertainty, questioning can be important to keep us from extreme positions that we don’t actually believe in. And that same uncertainty can be weaponised against us.

I’m afraid I do not have an easy, neat answer for you. I’m not sure I trust people who think they have easy, neat answers to these kinds of issues. But I do think our tradition gives us guiding principles, gives us values that should underlie our understanding of the world around us. I want to share two things with you today, two values that I feel are infused into the darkest texts of our Torah. One from Moses and one from Miriam.

First, Moses. In the middle of the worst we know of Pharaoh, having seen Pharaoh commit acts of infanticide, having seen Pharaoh reject the concept of freedom time and time again, God commands Moses: Bo el-Paroh. That’s where we get the name of our parashah from: Parashat “Bo”. It’s often translated as “go to Pharaoh”, but it doesn't mean that. It means “come to Pharaoh”. The place of God in the text is very different if God tells Moses to come to Pharaoh instead of go. Daniel Matt, mysticism scholar and Zohar translator, boils down the questions of the Zohar about that linguistic choice to this: “God was telling Moses, ‘Come to the nexus of the demonic and the divine.’”

The worst of the worst existed within Pharaoh. And yet, so did God. That’s the price we pay for being a people who believe that all humans are made b’tzelem Elokim, in the image of God. The Torah reminds us that Moses had to apply that principle to Pharaoh, even though Pharaoh doesn't believe in it, even in the fight of his life, even in the fight for freedom. It does not mean that nothing can be done. It does not mean that Moses has to capitulate to Pharaoh’s demands. What it does, I think, is remind us that when difficult decisions need to be made, they should be difficult.

Come to Pharaoh. But do not become him.

And that second piece, that second response I hear, is from Miriam. Miriam is silent in this parashah, but she was very present at the beginning of this story, and her presence will be felt again next week, in the celebration of redemption. One of the mysteries of Miriam is why she is a prophetess. The Torah does not explain her wearing of this title. I’ll be talking about that in ancient Mesopotamian context on Wednesday. But what we know about Miriam at the beginning of the Exodus narrative is that she is a child filled with hope.

There is a midrash in Sh’mot Rabbah which tells the story of the child Miriam rebuking her father. After the laws of infanticide are put into place, so says the midrash, Amram declared that he would divorce Yocheved. And the Israelite men followed his lead. After all, why should the Israelites continue to have children if Pharaoh declared that he would have the boys killed?

And the child Miriam stands up against her father and tells him that he is wrong. “Pharaoh decreed against the boys, and you are decreeing against the boys and the girls,” she says to her father. “Pharaoh is evil and his decree might not come to pass, but you are righteous, and your decree will.”

Here’s what I hear Miriam saying: by refusing to have hope, you are guaranteeing that Pharaoh will win. And she’s right. Where the adults are unable to see beyond the destruction in front of them, this little girl sees further: she sees the possibility of redemption on the other side, and she is willing to do the hard work to hold onto that. That’s why she leads the dance on the other side of the split sea. Because she has been waiting for it her entire life. Perhaps that is why she wears the title of prophet: her ability to maintain a sense that a future does exist, as long as we are willing to hope for it.

I have no easy medicine for the importance of, and danger of, uncertainty. It is just not as easy as correcting “mumpsimus” to “sumpsimus”. But I hear Our Teacher Moses saying in our text: stand up for what is right, and do it with a sense that all life is of inherent value. Refuse to give in to the narrative that some life is not worthwhile, because that is the position of Pharaoh, and we know what happened to Pharaoh’s heart.

And I hear Miriam the Prophet, ever-ready to dance in redemption, saying: the most important thing to nurture and maintain within ourselves is, and always will be, hope.

Comments

Post a Comment